Libros sobre cine

+33

Wolfchild138

le marchand de sable

hammerforever

Señor Perdido

Axlferrari

Floyd

Karlos

Jano

atila

Pamela Desbarres

Sean

ingeniero_pelotudo

dr hackenbush

®Lucy Lynskey

jackinthebox

Carlton Banks

from the mars hotel

BALEN

keith_caputo

Cowboy Bebop

Jevi Ochentero

Ricky´s Appetite

Joseba

Kirchhoff

Gregorio

Travis Bickle

slash2007

Phishead

deniztek

Rocket

el noi del sucre

Nashville

Barchi

37 participantes

Página 4 de 4.

Página 4 de 4. •  1, 2, 3, 4

1, 2, 3, 4

Re: Libros sobre cine

Re: Libros sobre cine

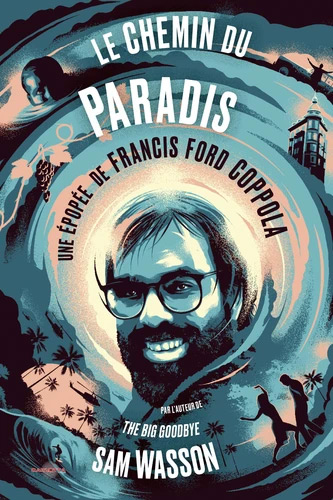

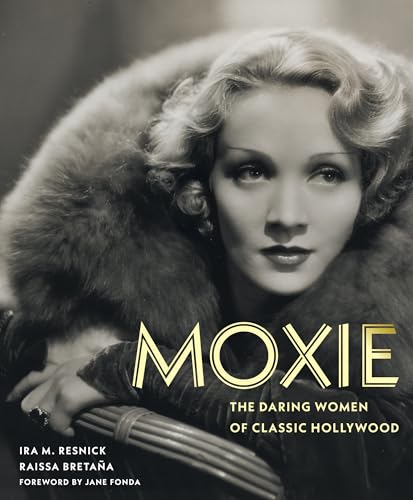

Ida Lupino, Filmmaker (2023)

Última edición por Axlferrari el 05.02.24 5:29, editado 3 veces

Re: Libros sobre cine

Re: Libros sobre cine

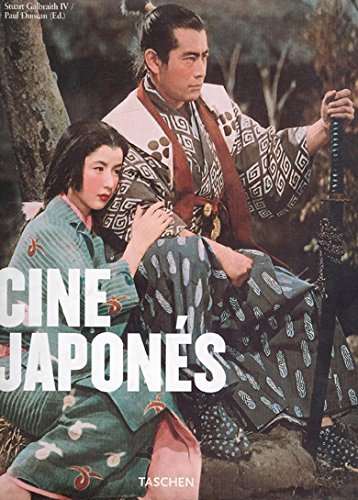

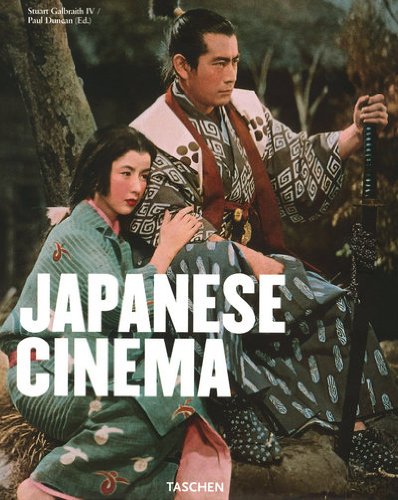

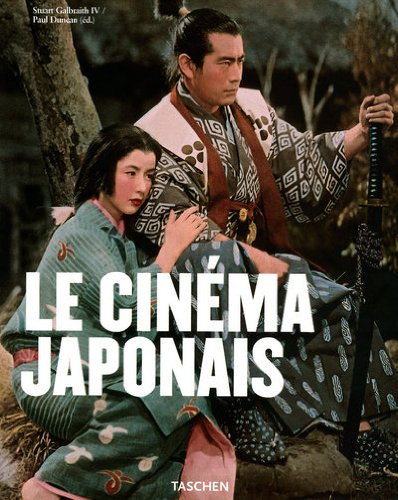

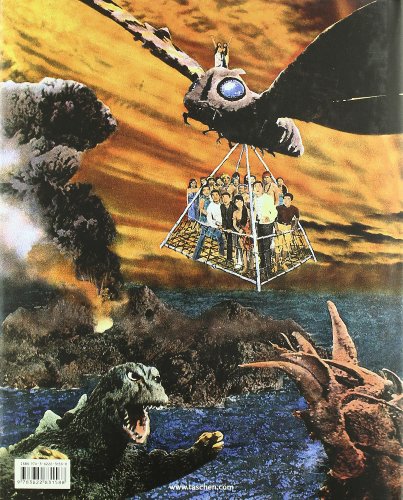

Stuart Galbraith y Paul Duncan, Cine japonés (descatalogado)

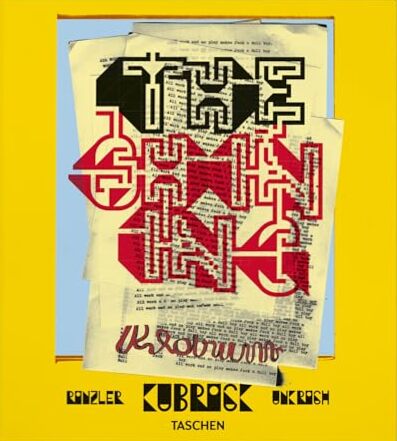

Taschen lanzó este libro de 2009 en varios idiomas :

- Spoiler:

Re: Libros sobre cine

Re: Libros sobre cine

Corriendo al kiosco en cuanto esté a la venta.

Dama de Shalott- Mensajes : 1033

Fecha de inscripción : 02/04/2022

Re: Libros sobre cine

Re: Libros sobre cine

Matthew Alford & Tom Secker, National Security Cinema

Basándose en archivos y numerosos testimonios, así como en análisis de películas, este libro revela las relaciones políticas y financieras que vinculan a Hollywood con el Pentágono y la CIA. A través de superproducciones financiadas por el Departamento de Defensa como Transformers, Terminator (no las dos primeras), las películas de Marvel o Top Gun, Alford demuestra cómo la industria cinematográfica se pone al servicio de una ideología pro-ejército que glorifica la imagen de Estados Unidos. Del mismo modo, las llamadas películas críticas (Tres reyes o Avatar), aunque de forma más sutil, cumplen una función similar.

Reseña en inglés :

- Spoiler:

Matthew Alford and Tom Secker's excellent book brilliantly exposes Hollywood's dirty - and not so little - secret: that the Pentagon and various intelligence agencies (mostly the Central Intelligence Agency) have a power, reach and influence in the development of films and television programmes, far beyond an "advisory / consultancy" basis.

National Security Cinema shows how a startlingly high number of mainstream media products, have been shaped to give favourable interpretations of United States foreign policy or public relations images of intelligence institutions and the military. Sometimes this is achieved through a simple quid pro quo: we'll let you film on a battleship / lend you helicopters etc and you give us authorisation over the portrayal of our institution.

It comes as no surprise that overtly military films like Black Hawk Down and Lone Survivor had a deep relationship with the military in their development, distorting and sometimes completely rewriting the actual events to put said organisation in a favourable light, or television series like Homeland. What is more disturbing is that fantasy material like the Transformers franchise, the later Terminator films (not the excellent first two) and even the Marvel Cinematic Universe films, have gone through development changes at the wishes of the Department of Defence.

What is also distressing is that, far from the military-industrial-intelligence complex having to engage in any arm-twisting or exerting leverage to get what they want out of Hollywood (though in some cases this is true: some films only got made because the army, navy or airforce was prepared to lend equipment or allow a military base as a shooting location and other films never got made because military support was not forthcoming), many writers, producers, directors and actors are only too willing to acquiesce to their demands and in many cases, actively seek this influence.

Authors Alford and Secker convincingly document and establish this through interviews as well as extensive use of the US Freedom of Information Act.

The authors also take time to look at those in the culture industry who have managed to resist the tentacles of National Security influence whilst making political statements: filmmakers like Oliver Stone and Paul Verhoeven.

National Security Cinema is a brilliant expose of a disturbing but little known and under-reported facet of the culture industry: so prevalent and powerful is the military-industrial-intelligence complex, embedded within Hollywood, that its output could be really called propaganda with out hyperbole. This book is highly recommended for those interested in how films are actually made (beyond the usual fluffy PR "making of...") and also for those who think Hollywood is run by a bunch of liberals.

Re: Libros sobre cine

Re: Libros sobre cine

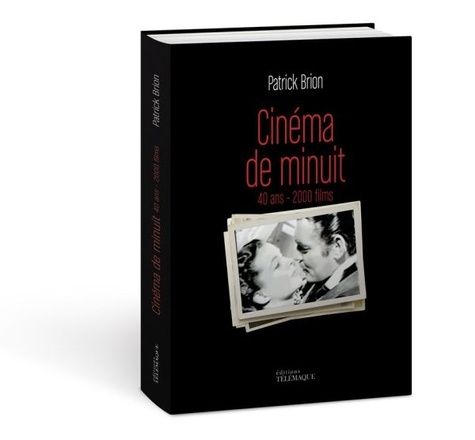

https://www.chasse-aux-livres.fr/prix/2753303223/cinema-de-minuit-2000-films

Otro libro monumental de Patrick Brion, casi 800 páginas con muchísimas fotos y una breve reseña para cada película (unas 2000).

La filmoteca ideal existe : desde hace 40 años, el "Cinéma de Minuit" (Cine de Medianoche) se la ofrece cada domingo por la noche en el canal France 3. 2.000 películas inéditas o poco conocidas, joyas raras u obras maestras indiscutibles del cine francés, italiano, inglés, americano, ruso, español o alemán... Dos mil veladas presentadas en el orden cronológico de su difusión desde marzo de 1976. Un universo de recuerdos intactos y emociones reencontradas. Un tesoro único del patrimonio cinematográfico mundial. 2.000 películas, más de 2.300 fotos y documentos.

Se incluyen todas las 2.000 películas presentadas en el programa Cine de Medianoche, con un comentario y una ficha técnica para cada una de ellas.

Por el mismo autor :

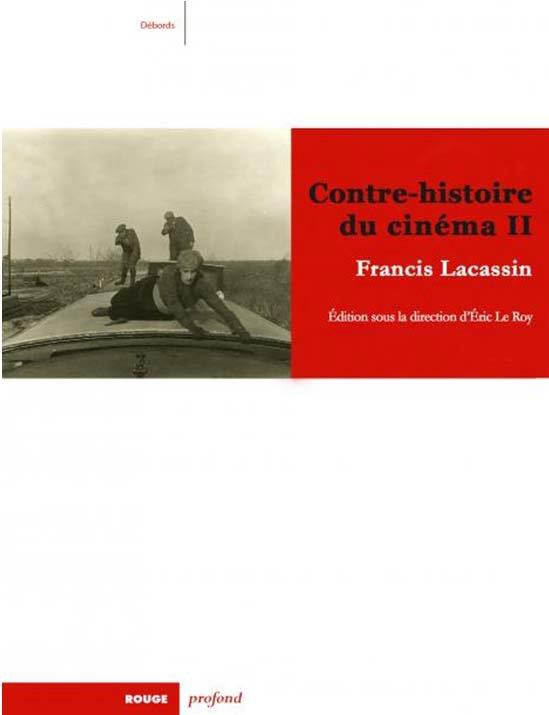

Novedad :

En 1972, Francis Lacassin publicó una "Contrahistoria del cine" para rehabilitar películas, cineastas, actores y actrices que habían caído en el olvido. En aquella edición, el autor imaginó secuelas. A partir de los resúmenes que dejó, he aquí el volumen 2 de su Contrahistoria del cine.

Y, como siempre, su original enfoque nos lleva entre bastidores de la creación y la producción, y nos desvela personajes fantasmagóricos, demasiado alejados de los focos y de la historia oficial. Así, nos toparemos con el cine cómico de los años 1910 con Roméo Bosetti, Onésime, los estudios de Épinay-sur-Seine o Niza, Louis Feuillade, y grandes mujeres del séptimo arte (Alice Guy, J. Bruno Ruby, Germaine Dulac, Marie-Louise Iribe...).

Re: Libros sobre cine

Re: Libros sobre cine

- Spoiler:

Gene Tierney, Self-portrait

Recreando el glamour del Hollywood de los años 40, la actriz habla de los papeles que ha interpretado, de los hombres ricos y famosos que la han cortejado, del fracaso de su primer matrimonio y de su lucha contra una enfermedad mental.

Gene Tierney: A Life of Pain and Sorrow - ReelRundown

Última edición por Axlferrari el 29.06.23 5:55, editado 1 vez

Re: Libros sobre cine

Re: Libros sobre cine

"1001 Películas que Hay Que Ver Antes de Morir"

Imprescindible recopilación muy bien detallada de la historia del cine aunque como se suele decir sobre gustos no hay nada escrito. Como opinión personal me faltan unas cuantas y me sobran bastantes.

Esta es la edición que tengo yo, la cual, si no recuerdo mal es del 2006

Imprescindible recopilación muy bien detallada de la historia del cine aunque como se suele decir sobre gustos no hay nada escrito. Como opinión personal me faltan unas cuantas y me sobran bastantes.

Esta es la edición que tengo yo, la cual, si no recuerdo mal es del 2006

Ju Ju Hound- Mensajes : 133

Fecha de inscripción : 31/05/2023

Re: Libros sobre cine

Re: Libros sobre cine

Novedad (está en inglés).

Archive is the first book by Sofia Coppola, covering the entirety of her singular and influential career in film. Constructed from Coppola’s personal collection of photographs and ephemera, including early development work, reference collages, influences, annotated scripts, and unseen behind-the-scenes documentation, it offers a detailed account of all eight of her films to date. Mapping a course from The Virgin Suicides (1999), through Lost in Translation (2003) and Marie Antoinette (2006), to The Beguiled (2017) and her upcoming feature Priscilla (fall 2023), exploring Priscilla Presley’s early years at Graceland, this luxurious volume reflects on one of the defining and most unmistakable cinematic oeuvres of the twenty-first century.

An art book personally edited and annotated throughout by Coppola, Archive offers an intimate encounter with her methods, references, and collaborators and an unprecedented insight into her working processes. Accompanying the highly personal images and texts from Coppola’s archive is an extended interview with renowned film journalist Lynn Hirschberg discussing the remarkable oeuvre they reflect. Designed by Joseph Logan and Anamaria Morris.

Re: Libros sobre cine

Re: Libros sobre cine

Novedad (en inglés) : The Deer Hunter, de Brad Prager.

Descripción del libro : https://www.livres-cinema.info/livre/20235/deer-hunter

Re: Libros sobre cine

Re: Libros sobre cine

¿Cuáles son los cinco mejores libros sobre cine jamás escritos?

Es la pregunta que el British Film Institute (BFI) le hizo a 51 críticos y escritores, aquí están sus respuestas :

The best film books, by 51 critics | Sight & Sound | BFI

Re: Libros sobre cine

Re: Libros sobre cine

El magnífico libro de Thoret sobre Michael Mann saldrá traducido en inglés en mayo de 2024.

Presentación :

"Con sólo once películas en su haber, Michael Mann ha conseguido trazar una línea singular e innovadora dentro de la industria de Hollywood. El Último Mohicano, Heat, The Insider, Ali, Collateral, Corrupción en Miami y Enemigos públicos han redistribuido las cartas del cine estadounidense hasta el punto de convertir a Mann en uno de los cineastas más importantes de las tres últimas décadas.

En pocos planos se puede identificar su estilo cinematográfico único : una predilección por los escenarios urbanos - y en particular por Los Ángeles, cuya imagen supo renovar - y los impresionantes planos nocturnos; un gusto por los hombres supremamente hábiles pero solitarios; una obsesión por el mundo del crimen; y, sobre todo, una forma contemplativa de filmar que combina fascinación y melancolía.

Más allá de un ensayo exhaustivo sobre la carrera de un cineasta revolucionario, este ensayo de Jean-Baptiste Thoret, es también un tratado sobre la época contemporánea."

Gravity of the Flux: Michael Mann’s Miami Vice

Magistral artículo en inglés de J.-B. Thoret que recoge toda la grandeza de Miami Vice, una de las películas más importantes de los últimos veinte años. Miami Vice no es una adaptación de la serie, es una obra maestra sobre la guerra capitalista contemporánea, la mundialización del crimen y los vínculos entre economía legal e ilegal. Mann consigue hacer un cine muy crítico con el capitalismo bajo una apariencia de blockbuster :

https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2007/feature-articles/miami-vice/

- Spoiler:

The Real is no more than the asymptomatic horizon of the Virtual.

– Jean Baudrillard, Le Pacte de lucidité ou l’intelligence du Mal (1)

Created by Anthony Yerkovitch and supervised (very) closely by Michael Mann, Miami Vice was, let’s remember, one of the leading television series of the 1980s and for the director of Heat (1995), chastened by the failure of The Keep (1983), the laboratory where he was going to forge a new æsthetic, founded on an extreme sophistication of mise en scène, an excessive taste for design and advertising kitsch (colour coding for each episode, Armani suits and moccasins for the heroes, etc.). One hundred and eleven episodes were shot between 1984 and 1989, with Don Johnson and Philip Michael Thomas in the roles of the sexiest and best-dressed cops in the history of television. From the credits, the tone is set: updated MTV and FM pop radio via the soundtrack (Phil Collins, Pat Benatar, Dire Straits, Bryan Ferry and electro-funk hits). The wings of pink flamingos in slow motion, tracking shots on gleaming limousines, an excess of bikinied bimbos, champagne flutes and dollar bills: in other words, the flashy universe of a series which, like Brian De Palma’s Scarface (1983) released one year earlier in theatres (and also set in Miami) and William Friedkin’s To Live and Die in L.A. (1985), was striving to paint the portrait of America in the 1980s, with its cult of individualism and money, of arrogant successes and cheap flashiness. Miami on the one hand, but Vice on the other: behind the yachts of the gangsters and their pastel-coloured palaces, a world infected by corruption and artifice, a carnivorous and swampy world for which the pet alligator of Sonny Crockett (Johnson) provides a limpid metaphor of America.

Finally, Michael Mann brings Miami Vice to the big screen and, in doing so, the greatest contemporary American filmmaker proves once again his ability to bend the logic of the blockbuster (Miami Vice was thus oversold) to his personal universe, to the extent that occasionally one has the impression of a brilliant re-routing of money (the film cost more than 150 million dollars) in favour of a radical work that does not give up its author’s formal and stylistic ambitions. Therefore, there is no consensus in its approach, but rather an extraordinary science of the alliance between the demands of the filmmaker and that of an art that is great only on the condition of remaining popular (the genre film, the foundation of all his films) – that is to say, the characteristic of the great American artists whose torch today Mann is one of the few to carry. Shot in HD video, a technique that Mann and his cameraman Dion Beebe pioneered in Collateral (2004), Miami Vice makes up first of all a novel sensory experience and, from a formal point of view, an inspired synthesis of impressionism and hyper-realism. The extreme graininess of the image, the heightened sensitivity of the light and the dilution of the colours confer on each shot a never-before-seen density on the cinema screen. A flash of lightning that stripes the sky, a palm tree that bends under the weight of the wind and an incandescent night that Mann’s camera relentlessly pursues convey the feeling of a hallucinatory film where man and nature dissolve in each other, quivering with the same tragic breath.

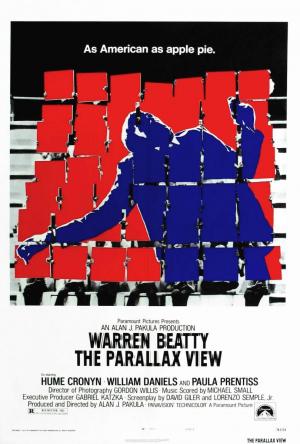

War Zone and Speed of Disappearance

On paper and in appearance, Miami Vice develops between a police story and a spy film and, before it blows up, the origin of its fiction is the murder of an FBI agent who has infiltrated the drug world. In order to solve the case, two Miami police detectives, James ‘Sonny’ Crockett (Colin Farrell) and Ricardo ‘Rico’ Tubbs (Jamie Foxx), pass as hardened drug dealers and make contact with the financial administration of a drug cartel, a vast organization endowed with staggering means. In a few minutes, Mann disposes of the picturesque approach of the genre (colourful gangsters, men with working-class hands, smooth talkers accompanied by a very definite bad taste) and composes a picture of the mafia with vague contours, a state-within-the-state equally at ease in the transfer of funds on a grand scale as in the clinical execution of offenders. At first sight, Michael Mann reconnects with the vein of the film-dossier of the 1970s, that of Three Days of the Condor (Sydney Pollack, 1975) and The Parallax View (Alan J. Pakula, 1974), a vein he already resumed with The Insider (1999), and re-employs his motif of identity reversals, his obsession with plot (who, from the FBI, CIA or Miami Dade, inhabits the traitor?) and his pervasive paranoia. But at bottom, Mann films this story of big-time trafficking like a high-tech war film where it is above all a question of logistics, an exchange of information, of surveillance and of technological mastery. Mann moreover repeatedly underlines the collusion between police and military techniques: on the way to a secret meeting place where Jesus Montoya (Luis Tosar), the big boss of the cartel, awaits them, Sonny and Ricardo realize that the drug traffickers use a system of electronic interference identical to the one employed by the CIA in Iraq. Finally, the film’s big shoot-out does not invert – as does Heat – the codes of a precise cinematographic genre (the Western), but rather is inspired directly by the imagery of war reportage: deafening and ultra-realist sound of weapons, moments captured live, discontinuity and partial illegibility of the action, proliferation of points of view (= suppression of a point of view), snipers in ambush.

Fascinating is first and foremost the way in which Mann, in total opposition to the classical treatment of narrative, rejects off-screen space or treats key moments of intrigue in sped-up motion (a war is told in snatches) and chooses to rest the great narrative knots of the film on details: a diamond watch illuminating the ambiguous relations between Isabella (Gong Li) and Jesus Montoya, or the discrete tear in the eye of Montaya’s heir apparent José Yero (John Ortis), by which we come to understand his deeper motives. The power of Miami Vice comes from its mix of formal elegance and brutality, of extreme stylisation and hyper-realism. Always both at once, they are in accordance with Mann’s great theorem: become the other in order to fight him, but at the risk, like the cop played by Colin Farrell, of losing one’s footing in an imprecise zone where nothing anymore allows reality to be distinguished from make-believe. Very quickly, the always-reassuring foundation of the genre, with its archetypes, its codes, its values and its outcome, collapses. The narrative develops then by jerks, flattens most of the peaks of action (the hold-up of the Haitian mafiosi settled in a few shots) and multiplies the false starts, as in the film’s opening, which concentrates on the arrest of a pimp, Neptune (Isaach De Bankole), then in a fraction of a second changes direction. Violence erupts in the shot, preceded by no ritual, blows up without forewarning and one enters into the film (no opening sequence, no title card) like a war reporter projected in the middle of a conflict in progress. Without beginning or end, it is just 135 breathless minutes deducted from an uninterrupted flux of images and events.

The first minutes impose a jerky and staggering movement, which the film, with the exception of the romantic interlude of the couple, Sonny and Isabella, in Havana, will not abandon. Everything mixes already, interior and exterior (Sonny goes from the interior of the night club to a roof in a continuous movement), public and private spheres (a short scene of Sonny flirting with a waitress, then an immediate return to the mission): Sonny and Ricardo’s first appearance seems to be the exact opposite of Neil McCauley (Robert De Niro) and Lt Vincent Hanna (Al Pacino) in Heat.

If amplitude and expansion inform the natural rhythm of Mann’s films up until now, Miami Vice takes place under the sign of compression, of the fragment, of speed and of breathlessness. Immersed in the milieu of night clubbers, already infiltrated, the two men emerge in the frame in a stroboscopic way. Between the dancers’ bodies, the movements of the crowd and the plasma screens, some rapid insert shots testify to their presence in the nightclub while the soundtrack juxtaposes, without the least wish for smooth mixing, three incomplete pieces, solely linked by the pounding of a same repetitive beat.

The opening ten minutes are enough for Mann to fix the rhythmic rules of Miami Vice: the event taking place will always matter more than the one that follows, whence the strange feeling of a film in pursuit of itself, obsessed by the next job, the action that follows. Filming with the camera on the shoulder gives the feeling, new in Mann, of a constant fragility of shots and, therefore, of what they show. It is as if each shot were thinking of two things at once – the event taking place (a deal, an arrest) and the event to come (the same over again) – and that the best way to not collapse consists of never staying still. In Miami Vice, it’s to be physically there, here and now, because mentally one is always and already elsewhere. The film is short-winded, in constant precocious ejaculation (a joke of Ricardo to his girlfriend Trudy (Naomie Harris) that reveals one of the principle motors of the film), Miami Vice possesses an immense but implosive energy which has nothing to do with the explosive energy of Mann’s earlier police films. (From this point of view, for the aborted sequence of the nightclub, Mann chooses a rigorously opposed treatment to that of the night club scene in Collateral.)

The jerky and convulsive narrative unfolds less according to a classical logic of development of sequences (dilation, edited in power and explosion) than of rampant compilation and short-circuits. The speed of the linking of the actions, their extreme compression, thus prevents the emergence of the feeling of a time that disappears, of a length that takes hold, in favour of a constant and monotonous topicality subservient to the law of “the here and now” – “Right now” the characters do not cease repeating throughout the film. But topicality is the opposite of time and the excess (of actions, of characters, of ramifications, of narrative lines, of narrative forks, etc.) is the mask of an omnipresent lack – lack of space, lack of the Other, lack of time, above all. “Time is luck”, says Isabella on several occasions to Sonny: a tragic refrain and curse of all of Mann’s heroes.

Surviving in the Flux

Miami Vice is above all a great film on the human condition in a time of flux. Everything progresses at top speed (the meetings, the love affairs, the reversals, the cars) but essentially nothing really moves forward. The general rumour of flux absorbs every modification of this flux, and dismisses events and characters with a noise from deep bottom. A trail of blood on the roadway (the suicide of the snitch, Alonzo (John Hawkes)), an echo on a radar or the noise of fingers snapping, are but nothing more than a short-lived imbalance of the global system. Whence the extraordinary and (paradoxical) inertia produced by a narrative so smitten with rapidity, as well as in the linking of sequences and shots, as in the execution of actions. The points of view become confused, the shots fall like unhooked links, but the general signal finishes by sweeping it along in the events that make it up. It traffics, it pulls, it circulates: Miami Vice is the point of flux against man’s point of view.

The use of HD allows Mann to forge a dense image, often opaque and viscous, which deepens the backgrounds and engulf the foregrounds. Thus, the characters gain in definition what they lose in contour, and thus in identity – visually, they free themselves with difficulty from the background and seem ceaselessly threatened with dissolution. This loss provokes an increased weight of the bodies (watch how they fall in the final shoot out), a constant swaying of space and, for the spectators, the feeling of a hypnotic pitching of shots. Deep water constitutes the primary substance of Miami Vice, a magmatic power that plays against the speed of the narrative and from which the individuals struggle and finally, failing that, they lose themselves. As a counterpoint to the chaos and confusion of human relations, Mann multiplies surface effects (bay windows, villas on the border of the sea) and sliding (off-shore, in the plane, in race cars). They are impeccable images from a world where survival depends on the capacity to remain on the surface (and superficial) and that allows consequently for only two positions: drowning (Sonny, the most infiltrated of the two) or weightlessness (Ricardo); either the temptation of the margin or the maintenance in the centre.

In the beginning of the film, Sonny and Ricardo pull-over Alonzo’s car, a snitch whose wife was just kidnapped. Sequence of panic on the edge of the highway: Alonzo wants to return home, see his wife and flee. “You don’t need to go home”, Ricardo says to him, since he knows it is already too late. Shot of Alonzo’s crushed face (“But they promised”), reverse shot on Ricardo’s (“They lied”). In the blurred passage from the cop’s face to the re-framing of the camera on the flow of the traffic, the man has thrown himself under a truck, leaving only a scarlet stain on the pavement. To become integrated in the flux is also to lose oneself therein.

The film closes as abruptly as it opened: Isabella escapes from the flux by the sea (the eternal utopia of Mann’s characters): “It’s magic”, says a fisherman about the sea near the beginning of Thief (1981), Sonny turns his back on the sea and returns to the flux. And loses himself therein. Life suspended on one side, perpetual flux on the other. No dead time or respite: the system runs at full speed but on empty, and possesses no other end than that of its own stability. To such an extent that one could, like Isabella, pass one’s entire life there: “It’s all that I know how to do; I’ve been doing that since I was 17”, she tells Sonny when the latter questions her on the possibility of an elsewhere, of an alternative life. The only thing that counts is the global balance of the system and its capacity to restore the unchanging order of things (disappearance of Jesus Montoya/death of Jose Yero, disappearance of Isabella/reappearance of Trudy, etc.). At bottom, between the beginning and the end of the film, nothing has changed. Like Frank (James Caan) at the end of Thief or Lowell Bergman (Al Pacino) in the last shot of The Insider, Sonny recedes in depth of the field, with his back to us, and disappears. In the world in flux that Miami Vice follows, the human is only an event, a lost atom in the multitude, similar to the one described by the hired killer in Collateral. It is either arrogance and/or naïveté of the couple, Sonny-Isabella, to have believed that the human could be stronger than the flux.

The men of Miami Dade only conform to the programs that pre-exist them, to respond to the electronic stimuli (a telephone call, a reaction). They turn out to be incapable of taking control of a disarticulated narrative that sometimes calls to mind, but in a less playful way, the game “Simon Says”, imagined by Jeremy Irons’ character in John McTiernan’s Die Hard: With a Vengeance (1995). Only Sonny manages it once with Isabella. You wouldn’t think it, and we’ll come back to it, but Miami Vice has also just laid the foundations for a new order of action films.

Identity of the World and of the Network

The post-urban (and post-human) world of Miami Vice is a confused, fragmented and controlled world that holds together only by the financial flux that crosses it and the electronic images (surveillance cameras, radars, computer screens, etc.) recreating the simulacrum. There is no other logic than that of offer and demand, of movement in all directions imposed by economic private interests. Little matter, then, whether the goods are legal or not, little matter, too, the nature of the market, since the film treats capitalism like a war (Jesus Montoya, the drug godfather, hooked on Bloomberg TV), with his exploitation of resources of the Third World (here, the Dominican Republic, Paraguay and Uruguay), the merciless elimination of rivals and its calculated violence. Impressive is the way in which Mann views the cartography of this world in flux, where one goes in the space of an edit from Brazil to Paraguay, from Miami to Geneva, but also from the Law to its underside, according to a logic of intensive and breathtaking permutation. The contemporary world such as the film describes is expressed in the sentiment of a generalized feeling, of an integral proximity of spaces and individuals, permitted by an ultra-sophisticated technological environment. It is a misleading proximity, since the solitude of beings (total in Miami Vice) gets worse as the virtual exchanges develop.

The idea of the network isn’t new in Mann’s cinema but it never reached this point of coincidence with the world. Already in Thief, Frank, independent burglar, knew how much his survival depended on his capacity to act outside of the Chicago mafia network. That is, until he swallows his motto (“My money goes in my pocket”) and accepts, for the sake of his family and his dreams, to make a deal with the Faust-like Leo (Robert Prosky). It is a fatal connection that ends in an immediate and devastating cataclysm of spaces (the jobs, his garage and his intimacy) that he had hitherto known how to partition. In Heat, no matter how much the frontiers between exterior and interior trembled, there still remains the possibility of taking shelter from the world. The friction between public and private spheres is frequent, the effects of one into another, but justly: the effects suppose an overstepping and consequently the existence of boundaries that are still active. It is moreover in organizing the alternation between one space and another, in exploiting this arrhythmia in the style of Jean-Pierre Melville, that Mann has forged his style, characterized by long contemplative stretches inserted in the heart of hyper-coded narratives (polar, adventure film, biopic, paranoid fiction, etc.).

In The Insider, the power of the network goes up a notch. Mann records the disappearance of the border separating the system (tobacco manufacturers) from the opposition (CBS, in fact, simple link in the great global economy), and confronted an old school journalist to a reticular cartography incipient in the heart of which this former student of Herbert Marcuse loses little by little his bearings. What is the secret at the hour of total transparence? Where does one place oneself when everyone is in the same boat? A first-rate response is issued by the CBS lawyer in the middle of the film, and which recalls that of Isabella in Miami Vice: “All that you see around you belongs to Jesus Montoya”, she says to Sonny who believes in the existence of an elsewhere. Does there exist a position exterior to the System? Otherwise, how to resist?

With Miami Vice, this tension between exterior and interior is completely reduced to the profit of a reticular world entirely subservient to the logic of the networks and the flux. Here, the spaces of resistance are disabled, almost nonexistent. Havana, haven of peace, is outside the flux and its exhausting topicality. In this sublime sequence, twelve minutes in weightlessness not a single one more, it is already time for Sonny to return (literally) to the dock. The counter space that Sonny and Isabella try to invent no longer holds together. Back in the flux, it explodes. The only possibility is to confuse the two, abolish the frontiers and submit to the rules of the network, like Ricardo and Trudy, lovers and co-workers. As Ricardo says to Alonzo: “You don’t need to go home” – and for a very good reason, because in Miami Vice home no longer exists. All that remains is an undifferentiated and homogenous zone, public and private, regulated and unstable.

The identity of the world and of the network explains why, according to a classical approach of the genre (undercover movie), what could have been one of the principal stakes of the film (How to preserve a cop’s false identity? How to make believe that one is another?) are settled very quickly. In Miami Vice, identity is no longer a question. “What difference is there between being infiltrated and being implicated up to your neck?”, as Ricardo more or less asks Sonny. The disconcerting facility with which the two cops shoulder the scheme of the complete Mafiosi expresses not only the indistinction of milieus but also the absolute reversibility of positions.

The fact that the priority is that of the network and not that of individuals implies the possibility of hiding oneself there, of disappearing in the intangible space of the Virtual and so to be nowhere located, which solves all problems of identity, not to mention the problems of alterity. (2)

An immense step is taken here from Heat, which, despite the impression of resemblance between the cop Hanna and the gangster McCauley, protects and maintains intact a principle of alterity, a difference of nature vis à vis the Law that prevents Mann from framing them together. (3) Heat was a film on reflection, the mirror effect, the temptation of the Other; Miami Vice is a film on confusion, indistinction and the equivalence of opposites. The cop is no longer the reversed double of the drug dealer, but his distant echo, his replica, even if on his last legs, Michael Mann once again half opens the door onto a world (Heat, the classic police story, the Law and its underside) in the process of becoming extinct. In Miami Vice, infiltration does not constitute an infringement of the general Law of a global system that has resolved contradictions and confused positions. In this obscure indecipherable without limits, what one really is (a cop, a crook) no longer matters. The only thing that counts is the trace that one leaves in the system, the stamp that one leaves there: back in Colombia where they have come to settle their first mission as carriers, Sonny and Ricardo fly a plane filled with drugs that is hidden in the wake of an official plane. Two distinct signals appear on the air control screen, two circles that overlap briefly before merging; two different engines for the radar, a single image. What difference is there between the Law and its underside? None, “Just a ghost”, says one of the radar controllers. No matter the differences as soon as one discharges the same image.

In Miami Vice, the image is not deduced from reality, but reality from the image. It is by it (parallel trajectories of two off-shore planes filmed at night) that Sonny and Ricardo identify the supplier who helps them to integrate into the Organization, it is by it again (two bodies intertwined on a dance floor) that Montoya understands the relation that unites Sonny and “his Isabella”, it is again it (the infra-red image of Jose Vero’s snipers that Lieutenant Castillo locates) that gives the send off for the final shoot-out.

The classical/modern conflict, essential in Mann, takes here an unexpected turn and puts Miami Vice undoubtedly at the origin of a new cycle in Mann’s work. The question is no longer, as in Manhunter (1986) or Heat, to evaluate what between two worlds is similar or different since, if disparity remains, it is in a negligible manner. From this point of view, classicism with its strong events (hold-ups, shoot-outs, marked positions, etc.), its simplification of the stakes and its resolution of an initial given situation is consumed: the leak in the heart of a governmental agency that launched the narrative will never be identified, the romance between Isabella and Sonny appears suddenly on the way and finally takes the upper hand, while, at the end, Montoya vanishes. From modernity and from American cinema of the 1970s, Miami Vice has kept a problematic rapport to action, between deflating (how many dismissed sequences and aborted conclusions) and overheating. But there is also the feeling of a complex and illegible world, in which it has become impossible to interact if not in a peripheral manner (the release of Trudy from the claws of the Aryen brothers, the elimination of Yero, etc.). The film progresses (too) quickly, but at a constant rhythm (which is to say the contrary of a classical temporality), as if nothing could carry it away or slow it down. The network demands it, the world of Miami Vice has lost its centre of gravity and seems devoted to a paradoxical movement: illusion of speed (or rather haste) but effect of being stuck. Heat and Collateral were centred around a dual relationship: two couples of characters – Hanna-McCauley and Vincent (Tom Cruise)-Max (Jamie Foxx) – whose intertwining constitutes the subject of the films, the point of equilibrium towards which they inexorably converge. Around what centre does Miami Vice turn? What finally is its point of anchoring?

Sonny and Isabella, The Axis of Desire

At the beginning of the film, in a villa that looks like an aquarium, a long discussion gets under way between the Miami Dade team and Nicholas (Eddie Marsan), a dealer connected to the mafia’s multinational company. The goal: to put Sonny and Ricardo in contact with members of the cartel. Standing near a bay window, Sonny leaves the conversation for a brief moment and turns towards the ocean. It’s a moment of existential solitude characteristic of Mann’s cinema (silence on the soundtrack, gaze lost on the horizon) that already indicates the desire of the character to extricate himself from the flux, to reinvent lost time. Sonny is the desire of an elsewhere, the perpetual will to disconnect from the world, mentally as well as physically, as the escapade at Havana testifies. After the ideal image of the American dream (Thief), the Fiji Islands (Heat) and the postcard of the Maldives (Collateral), Sonny embodies in his turn the Mannian imaginary of a mental and geographical extension, of a utopic elsewhere that the film will never realize but whose simulacrum it will fabricate (Havana). The two cops thus embody two divergent movements. Ricardo takes care of the police story and assures its upkeep; he is the man of stability (both in his love life and professionally) and of the centre. Sonny, on the other hand is unpredictable and instinctive; he carries in him a desire for rupture, deviation, and unbalance.

Ciudad del Este, on the border between Paraguay, Brazil and Argentina. It is the first test for Sonny and Ricardo in the skin of hardened drug runners. The test of force takes place in a dark warehouse, typical space of the underworld and its secret activities. Facing them is José Yero, Montoya’s right-hand man and first cog of the multinational company. The confrontation between the three men dictates the editing of the sequence (shot/reverse-shot and establishing shots that stress the presence of over-armed doormen) but their discussion deteriorates to a point of impasse. Suddenly, somewhere in the surrounding area of this little theatre of shadows, a voice, imperial and authoritative, emerges off-screen, straight away relayed by a horizontal movement of camera that reveals the presence of a woman (already there, but invisible until then). The first appearance of Isabella in the film imposes a decentring of the sequence (from José Yero to this woman in the impeccable suit). Like Sonny a few minutes earlier, Isabella remains aloof, on the edge of the frame, and provokes the displacement of the shot towards its margins.

From this point of view, the Havana sequence only achieves what the mise en scène (two identical desires, thus two ways of occupying the frame) anticipated. The couple then becomes scarce in relation to a narrative that the film, for twelve minutes, leaves in suspense. Mann then stresses at length their trip, from the coast of Florida to that of Havana: time relaxes, the distances hollow out space again. Their breakaway functions like a gasp of air, an attempt to recover a space against the flux, against topicality, even if, as Olivier Mongin writes in La Condition urbaine: “Places can only be the underside/reverse of flux, a make believe, a simple existential haven, a cell destined to regain one’s breath, a retreat where the vita activa is banished.” (4) It is an insular sequence. The future and the past, projects become once again between them topics of discussion. In disconnecting from topicality (and from technology, not the slightest ring of the telephone), the film reconnects to the past, to History, to memories, and finds again (condenses) something of the respiration of Mann’s previous films: Isabella has revealed snippets of her childhood, shows a photo of her mother to Sonny, recalls her origins; Sonny speaks to her of their future, of what she contemplates doing after. Flux is technology and technology (a major acquisition of paranoid fictions of the 1970s: see the opening sequence of Three Days of the Condor) is death: it is the literal equivalence of the explosion of the mobile home, set off by Yero’s mobile phone.

How can man hold on in a disembodied world, so transparent but ultimately so opaque? The disappearance of the human, its dematerialization in the heart of an urban universe governed by technology, and thus its capacity for resistance, constitutes one of the central themes of Mann’s cinema and finds in Miami Vice its most accomplished extension. Here, the only point of view capable of reversing the flux is in the Sonny-Isabella axis. When their eyes connect, immediately the world recedes and the flux subsides. On the port of Baranquilla in Colombia, the transfer of goods recedes to the background as soon as Isabella appears in the shot, looking for Sonny’s eyes. In the same way, the final gunfight goes from foreground to background exactly when Isabella discovers the badge (and identity) of Sonny. Without the woman, the man is nothing. If he loses this ballast, he falls (Alonzo’s suicide, return to the flux and darkness for Sonny at the end of the film); if he finds her again, he remains on the surface (Trudy comes out of a coma and Ricardo wakes up). But Isabella isn’t the only one to hold this power of aspiration and de-framing. In Miami Vice, women are the only ones to possess the power to divert the narrative (Yero’s jealousy, secretly in love with Isabella), to calm it (amorous sequence between Ricardo and Trudy) or to speed it up (Trudy taken hostage; Lonetta’s death). From the first sequence, Mann expressly makes women the pivot of all the swerves: the silhouette of a dancer against a background of electronic images, a conscious pick-up by Sonny of the waitress, the deal between a pimp and his client, and the murder of the wife of an informer.

The scales of the film tip in a no-man’s land in the middle of which two cops finally meet Jesus Montoya. But Ricardo and Sonny do not have the same reading of the sequence: the first concentrates on the drug godfather, on his orders and the information he delivers, while the second sees only Isabella and the relation (two watches with identical diamonds) which, he believes, connects her to Montoya. Ricardo remains tied to the fiction of the genre Sonny gives up, sucked up by this woman who looks like an icon. When she moves away in the car, Sonny’s gaze remains fixed on her and finds at last the axis of its desire: the only bright trace at the heart of this indecipherable night, point of sublime anchoring and dazzling gap, Isabella appears like the image of a possible elsewhere. But it’s only an image (the rectangle formed by the window pane).

In the last sequence of the film, Sonny takes Isabella to a house by the sea, a deserted hideaway where a boat is waiting. Of their story, there remains nothing more than two faces framed in close-up, turned towards a horizon henceforth blocked. “It was too good to last,” he says. Isabella takes off, alone, glancing one last time at Sonny. But no reverse shot is forthcoming: Sonny, already into his car, moves away and the optical axis that they formed together suddenly breaks. It is the moment to return to the flux. To give in. The world rediscovers its balance but loses a little more of its humanity. One of Sonny’s replies to Isabella comes to mind: “We can do nothing against gravity.” In other words, there is nothing to be done against the flux, except to extricate oneself for a short while. We end up always by going back to it and dissolving therein (the last shot of the film). Sonny: “We have no future.” Here, no more deeply glistening marine seaweed (Heat), no more Maldives to refresh the eyes (Collateral), no more photographic dream to realize (Thief), in Miami Vice the elsewhere is a lost cause. And melancholy is the only way of living on a long-term basis in the world.

“One of these mornings / Won’t be very long / You will look for me / And I’ll be gone”, Patti LaBelle sings to the music of Moby at the beginning of their story – Isabella and Sonny on the way to Havana – but already its end.

Endnotes

1. Jean Baudrillard, translated by Chris Turner, The Intelligence of Evil or the Lucidity Pact (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005).

2. Jean Baudrillard, Le Pacte de lucidité ou l’intelligence de Mal, translation by S. Shafto.

3. On this topic, see my article, “Trajectories incompatibles”, in Panic 1, November 2005.

4. Olivier Mongin, La Condition humaine: la ville à l’heure de la mondialisation (Paris: Seuil, 2005).

Un homenaje al cine de Michael Mann : https://vimeo.com/132708938

Otro buen vídeo :

Re: Libros sobre cine

Re: Libros sobre cine

Presentación de la editorial : https://www.livres-cinema.info/livre/21754/films-of-lucrecia-martel

Lucrecia Martel sólo ha rodado cuatro largometrajes hasta la fecha, pero se ha convertido en una de las directoras más admiradas del mundo. Su obra es extraordinariamente sensible a los límites de la percepción sensorial, los límites impuestos por los roles de género y los límites de la empatía y el afecto a través de las divisiones sociales.

Esta recopilación amplía el debate crítico en torno a la obra de Martel al integrar el análisis de sus largometrajes con el de sus cortometrajes, menos estudiados, y sus otros proyectos artísticos. El enfoque fresco y holístico de este volumen sobre la carrera de Martel incluye contribuciones de estudiosos de América Latina, Europa y Estados Unidos, y termina con una nueva entrevista con la propia Martel.

Re: Libros sobre cine

Re: Libros sobre cine

Brett Davies acaba de publicar en inglés este libro sobre Lawrence Kasdan.

Presentación : https://www.livres-cinema.info/livre/21721/films-of-lawrence-kasdan

El libro analiza críticamente la obra del cineasta y guionista estadounidense Lawrence Kasdan. Considera los contextos industrial, cultural y político, revelando cómo la obra de Kasdan ha influido -y ha sido influida- por la sociedad estadounidense en general.

Aporta pruebas de la importante contribución de Kasdan a la creación de la saga de La guerra de las galaxias y, por extensión, a la narrativa cinematográfica moderna.

Lawrence Kasdan ha creado algunas de las películas más influyentes de la historia de Hollywood. Es el guionista de éxitos de taquilla tan queridos como El imperio contraataca (1980), En busca del arca perdida (1981), El guardaespaldas (1992) y El despertar de la Fuerza (2015). Al mismo tiempo, ha sido aclamado por la crítica como director de películas que diseccionan la sociedad estadounidense contemporánea: Body Heat (1981), The Big Chill (1983), The Accidental Tourist (1988) y Grand Canyon (1991).

Part I: "I'm making this up as I go" Lawrence Kasdan and Raiders of the Lost Ark

Chapter 1. Smith and Jones: Discourse Analysis of the Raiders of the Lost Ark Story Conference

Chapter 2. Visual Language in the Raiders of the Lost Ark Screenplay

Part II: Kasdan the Director: Developing Style(s)

Chapter 3. Body Heat: Heightened Style in the Neo-Noir

Chapter 4. Classical Structure in the "Perfect Ensemble" of The Big Chill

Part III: Voice of the Largest Generation

Chapter 5. Altruism and Otherness in The Big Chill, The Accidental Tourist, and Grand Canyon

Chapter 6. Cowboys, Aliens, and Sixtysomethings: Age and Nostalgia in Kasdan's Later Films

Part IV: Influences, Without and Within

Chapter 7. From Noir to Kurosawa: Allusion and Homage in Lawrence Kasdan's Films

Chapter 8. Kasdan's Collaborations: Creation and Performance

Part V: A Long Time in a Galaxy Far, Far Away

Chapter 9. From Star Wars to Saga: Lawrence Kasdan and The Empire Strikes Back

Chapter 10. Revenge of the Monomyth: Reclaiming the Hero's Journey in Return of the Jedi

Chapter 11. A New Hope in The Force Awakens

Chapter 12. A Changed Man: Solo and Beyond

Chapter 13. An Interview with Lawrence Kasdan

Re: Libros sobre cine

Re: Libros sobre cine

Peter Bogdanovich, John Ford

Se trata de una reimpresión revisada y aumentada en 1992 de la obra original publicada en 1967.

Con una biografía de John Ford, unas 70 páginas de entrevistas con Ford y una filmografía.

Re: Libros sobre cine

Re: Libros sobre cine

Go West, el nuevo libro del gran crítico Michel Ciment, fallecido en 2023, consiste en una recopilación de entrevistas con directores norteamericanos : Livre : Go West (livres-cinema.info)

https://www.fnac.com/a19430481/Michel-Ciment-Go-West

El editor Julien Magnani estuvo muy implicado en la preparación del libro :

Conocí a Michel Ciment después de publicar Qu'elle était verte ma vallée, de Jean-Baptiste Thoret, en enero de 2021. A Michel Ciment le había gustado mucho el libro y quería presentarlo en su revista Positif. A pesar de mi cinefilia, debo admitir que en aquel momento sabía muy poco de la historia y los protagonistas de Positif (la gran revista francesa de cine de la que Michel era figura tutelar, pilar de la cinefilia internacional, revista hermana y rival de Cahiers du Cinéma).

No sabía nada de la obra de Michel Ciment. Conocerle me permitió descubrir la revista Positif, todo su trabajo y, sobre todo, la obra y los libros de Michel. Me conmovió mucho su enfoque ecléctico y humanista del cine, su gran delicadeza, su curiosidad y su interés por todas las artes que rodean al cine... También le interesaban mucho los libros publicados por nuestra editorial Magnani.

Animado por Jean-Baptiste Thoret, le propuse a Michel seguirle como editor. Compartiendo mi pasión por el cine americano, Michel me propuso recopilar sus entrevistas con las distintas generaciones de cineastas de Hollywood (publicadas anteriormente en la revista Positif): de Fritz Lang a Quentin Tarantino. "Go West" presenta una selección de todas estas fascinantes entrevistas y, sobre todo, representa el itinerario de Michel Ciment con los directores americanos a lo largo de unos cincuenta años.

Como editor, me gustaría utilizar "Go West" de Michel Ciment para compartir con las nuevas generaciones de cinéfilos, así como con los cinéfilos más veteranos, toda la historia de Michel Ciment, de la revista Positif, de esta parte de la cinefilia, reconocida en todo el mundo, pero que hoy se enfrenta al reto permanente de transmitir conocimientos en una historia de las formas socavada por la industria ultracultural y su sobreproducción, la amnesia que arrastra consigo y su dictadura del presente.

No hay películas antiguas, libros antiguos o autores antiguos; sólo obras e individuos que no hemos leído. Michel Ciment fue ante todo un intermediario, dando su tiempo y su trabajo a cineastas que no siempre eran los más reconocidos por la crítica o la taquilla; a menudo ayudó a rehabilitar o a obtener el reconocimiento de obras cinematográficas que no habían podido consolidarse suficientemente; enseñándonos de paso que una obra es tan importante como el interés que suscita en una comunidad de individuos, de Luces, tan preciadas para sus contemporáneos y las generaciones futuras. Luces que hoy nos corresponde mantener encendidas avanzando siempre hacia adelante, hacia lo que aún no sabemos, no conocemos.

Re: Libros sobre cine

Re: Libros sobre cine

Nick Tosches, Dino

"No es una retrospectiva, es una panorámica."

Ya falta poco (23 de mayo) :

Axlferrari escribió:

- Spoiler:

El magnífico libro de Thoret sobre Michael Mann saldrá traducido en inglés en mayo de 2024.

- Spoiler:

Presentación :

"Con sólo once películas en su haber, Michael Mann ha conseguido trazar una línea singular e innovadora dentro de la industria de Hollywood. El Último Mohicano, Heat, The Insider, Ali, Collateral, Corrupción en Miami y Enemigos públicos han redistribuido las cartas del cine estadounidense hasta el punto de convertir a Mann en uno de los cineastas más importantes de las tres últimas décadas.

En pocos planos se puede identificar su estilo cinematográfico único : una predilección por los escenarios urbanos - y en particular por Los Ángeles, cuya imagen supo renovar - y los impresionantes planos nocturnos; un gusto por los hombres supremamente hábiles pero solitarios; una obsesión por el mundo del crimen; y, sobre todo, una forma contemplativa de filmar que combina fascinación y melancolía.

Más allá de un ensayo exhaustivo sobre la carrera de un cineasta revolucionario, este ensayo de Jean-Baptiste Thoret, es también un tratado sobre la época contemporánea."

Gravity of the Flux: Michael Mann’s Miami Vice

Magistral artículo en inglés de J.-B. Thoret que recoge toda la grandeza de Miami Vice, una de las películas más importantes de los últimos veinte años. Miami Vice no es una adaptación de la serie, es una obra maestra sobre la guerra capitalista contemporánea, la mundialización del crimen y los vínculos entre economía legal e ilegal. Mann consigue hacer un cine muy crítico con el capitalismo bajo una apariencia de blockbuster :

https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2007/feature-articles/miami-vice/

- Spoiler:

The Real is no more than the asymptomatic horizon of the Virtual.

– Jean Baudrillard, Le Pacte de lucidité ou l’intelligence du Mal (1)

Created by Anthony Yerkovitch and supervised (very) closely by Michael Mann, Miami Vice was, let’s remember, one of the leading television series of the 1980s and for the director of Heat (1995), chastened by the failure of The Keep (1983), the laboratory where he was going to forge a new æsthetic, founded on an extreme sophistication of mise en scène, an excessive taste for design and advertising kitsch (colour coding for each episode, Armani suits and moccasins for the heroes, etc.). One hundred and eleven episodes were shot between 1984 and 1989, with Don Johnson and Philip Michael Thomas in the roles of the sexiest and best-dressed cops in the history of television. From the credits, the tone is set: updated MTV and FM pop radio via the soundtrack (Phil Collins, Pat Benatar, Dire Straits, Bryan Ferry and electro-funk hits). The wings of pink flamingos in slow motion, tracking shots on gleaming limousines, an excess of bikinied bimbos, champagne flutes and dollar bills: in other words, the flashy universe of a series which, like Brian De Palma’s Scarface (1983) released one year earlier in theatres (and also set in Miami) and William Friedkin’s To Live and Die in L.A. (1985), was striving to paint the portrait of America in the 1980s, with its cult of individualism and money, of arrogant successes and cheap flashiness. Miami on the one hand, but Vice on the other: behind the yachts of the gangsters and their pastel-coloured palaces, a world infected by corruption and artifice, a carnivorous and swampy world for which the pet alligator of Sonny Crockett (Johnson) provides a limpid metaphor of America.

Finally, Michael Mann brings Miami Vice to the big screen and, in doing so, the greatest contemporary American filmmaker proves once again his ability to bend the logic of the blockbuster (Miami Vice was thus oversold) to his personal universe, to the extent that occasionally one has the impression of a brilliant re-routing of money (the film cost more than 150 million dollars) in favour of a radical work that does not give up its author’s formal and stylistic ambitions. Therefore, there is no consensus in its approach, but rather an extraordinary science of the alliance between the demands of the filmmaker and that of an art that is great only on the condition of remaining popular (the genre film, the foundation of all his films) – that is to say, the characteristic of the great American artists whose torch today Mann is one of the few to carry. Shot in HD video, a technique that Mann and his cameraman Dion Beebe pioneered in Collateral (2004), Miami Vice makes up first of all a novel sensory experience and, from a formal point of view, an inspired synthesis of impressionism and hyper-realism. The extreme graininess of the image, the heightened sensitivity of the light and the dilution of the colours confer on each shot a never-before-seen density on the cinema screen. A flash of lightning that stripes the sky, a palm tree that bends under the weight of the wind and an incandescent night that Mann’s camera relentlessly pursues convey the feeling of a hallucinatory film where man and nature dissolve in each other, quivering with the same tragic breath.

War Zone and Speed of Disappearance

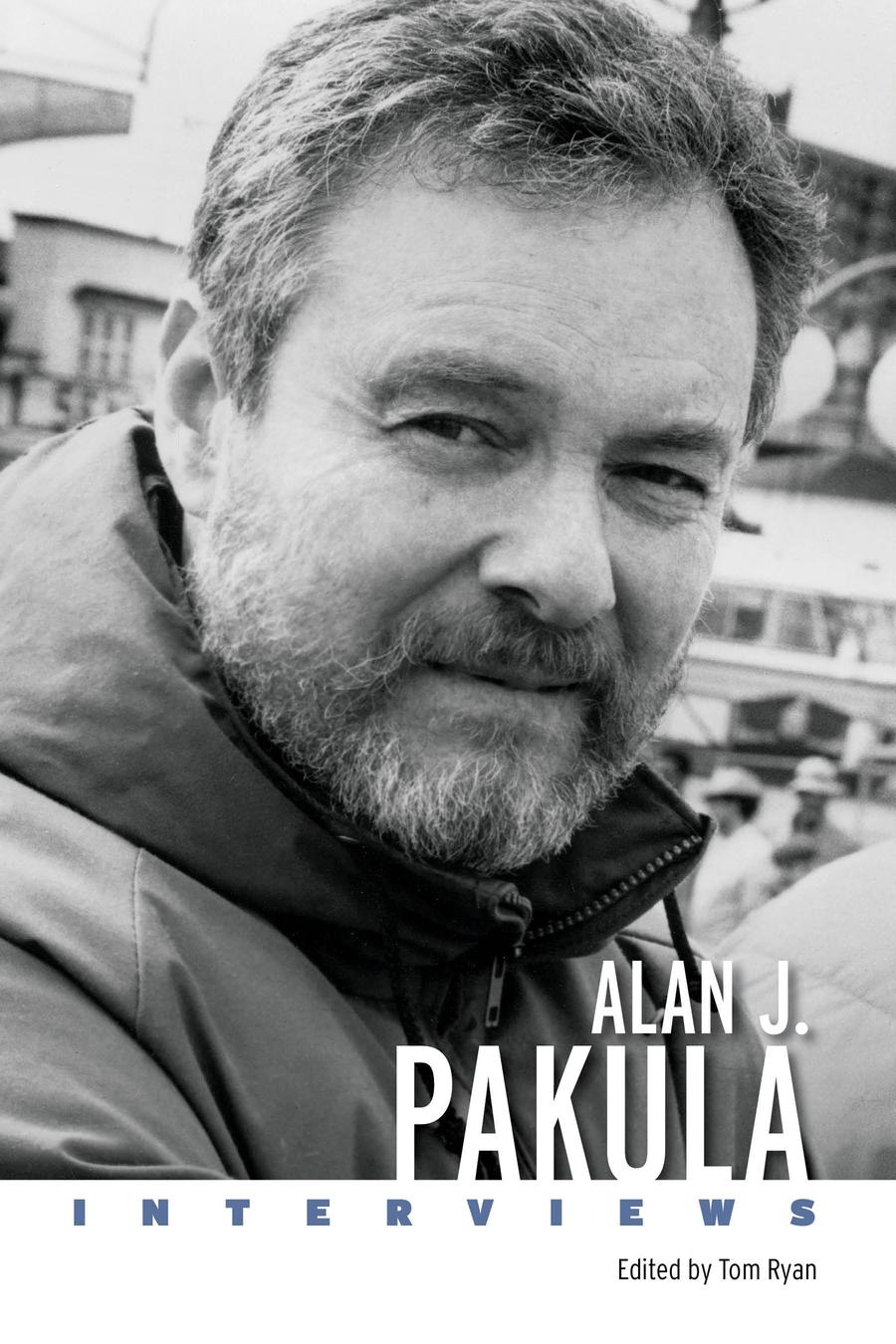

On paper and in appearance, Miami Vice develops between a police story and a spy film and, before it blows up, the origin of its fiction is the murder of an FBI agent who has infiltrated the drug world. In order to solve the case, two Miami police detectives, James ‘Sonny’ Crockett (Colin Farrell) and Ricardo ‘Rico’ Tubbs (Jamie Foxx), pass as hardened drug dealers and make contact with the financial administration of a drug cartel, a vast organization endowed with staggering means. In a few minutes, Mann disposes of the picturesque approach of the genre (colourful gangsters, men with working-class hands, smooth talkers accompanied by a very definite bad taste) and composes a picture of the mafia with vague contours, a state-within-the-state equally at ease in the transfer of funds on a grand scale as in the clinical execution of offenders. At first sight, Michael Mann reconnects with the vein of the film-dossier of the 1970s, that of Three Days of the Condor (Sydney Pollack, 1975) and The Parallax View (Alan J. Pakula, 1974), a vein he already resumed with The Insider (1999), and re-employs his motif of identity reversals, his obsession with plot (who, from the FBI, CIA or Miami Dade, inhabits the traitor?) and his pervasive paranoia. But at bottom, Mann films this story of big-time trafficking like a high-tech war film where it is above all a question of logistics, an exchange of information, of surveillance and of technological mastery. Mann moreover repeatedly underlines the collusion between police and military techniques: on the way to a secret meeting place where Jesus Montoya (Luis Tosar), the big boss of the cartel, awaits them, Sonny and Ricardo realize that the drug traffickers use a system of electronic interference identical to the one employed by the CIA in Iraq. Finally, the film’s big shoot-out does not invert – as does Heat – the codes of a precise cinematographic genre (the Western), but rather is inspired directly by the imagery of war reportage: deafening and ultra-realist sound of weapons, moments captured live, discontinuity and partial illegibility of the action, proliferation of points of view (= suppression of a point of view), snipers in ambush.

Fascinating is first and foremost the way in which Mann, in total opposition to the classical treatment of narrative, rejects off-screen space or treats key moments of intrigue in sped-up motion (a war is told in snatches) and chooses to rest the great narrative knots of the film on details: a diamond watch illuminating the ambiguous relations between Isabella (Gong Li) and Jesus Montoya, or the discrete tear in the eye of Montaya’s heir apparent José Yero (John Ortis), by which we come to understand his deeper motives. The power of Miami Vice comes from its mix of formal elegance and brutality, of extreme stylisation and hyper-realism. Always both at once, they are in accordance with Mann’s great theorem: become the other in order to fight him, but at the risk, like the cop played by Colin Farrell, of losing one’s footing in an imprecise zone where nothing anymore allows reality to be distinguished from make-believe. Very quickly, the always-reassuring foundation of the genre, with its archetypes, its codes, its values and its outcome, collapses. The narrative develops then by jerks, flattens most of the peaks of action (the hold-up of the Haitian mafiosi settled in a few shots) and multiplies the false starts, as in the film’s opening, which concentrates on the arrest of a pimp, Neptune (Isaach De Bankole), then in a fraction of a second changes direction. Violence erupts in the shot, preceded by no ritual, blows up without forewarning and one enters into the film (no opening sequence, no title card) like a war reporter projected in the middle of a conflict in progress. Without beginning or end, it is just 135 breathless minutes deducted from an uninterrupted flux of images and events.

The first minutes impose a jerky and staggering movement, which the film, with the exception of the romantic interlude of the couple, Sonny and Isabella, in Havana, will not abandon. Everything mixes already, interior and exterior (Sonny goes from the interior of the night club to a roof in a continuous movement), public and private spheres (a short scene of Sonny flirting with a waitress, then an immediate return to the mission): Sonny and Ricardo’s first appearance seems to be the exact opposite of Neil McCauley (Robert De Niro) and Lt Vincent Hanna (Al Pacino) in Heat.

If amplitude and expansion inform the natural rhythm of Mann’s films up until now, Miami Vice takes place under the sign of compression, of the fragment, of speed and of breathlessness. Immersed in the milieu of night clubbers, already infiltrated, the two men emerge in the frame in a stroboscopic way. Between the dancers’ bodies, the movements of the crowd and the plasma screens, some rapid insert shots testify to their presence in the nightclub while the soundtrack juxtaposes, without the least wish for smooth mixing, three incomplete pieces, solely linked by the pounding of a same repetitive beat.

The opening ten minutes are enough for Mann to fix the rhythmic rules of Miami Vice: the event taking place will always matter more than the one that follows, whence the strange feeling of a film in pursuit of itself, obsessed by the next job, the action that follows. Filming with the camera on the shoulder gives the feeling, new in Mann, of a constant fragility of shots and, therefore, of what they show. It is as if each shot were thinking of two things at once – the event taking place (a deal, an arrest) and the event to come (the same over again) – and that the best way to not collapse consists of never staying still. In Miami Vice, it’s to be physically there, here and now, because mentally one is always and already elsewhere. The film is short-winded, in constant precocious ejaculation (a joke of Ricardo to his girlfriend Trudy (Naomie Harris) that reveals one of the principle motors of the film), Miami Vice possesses an immense but implosive energy which has nothing to do with the explosive energy of Mann’s earlier police films. (From this point of view, for the aborted sequence of the nightclub, Mann chooses a rigorously opposed treatment to that of the night club scene in Collateral.)

The jerky and convulsive narrative unfolds less according to a classical logic of development of sequences (dilation, edited in power and explosion) than of rampant compilation and short-circuits. The speed of the linking of the actions, their extreme compression, thus prevents the emergence of the feeling of a time that disappears, of a length that takes hold, in favour of a constant and monotonous topicality subservient to the law of “the here and now” – “Right now” the characters do not cease repeating throughout the film. But topicality is the opposite of time and the excess (of actions, of characters, of ramifications, of narrative lines, of narrative forks, etc.) is the mask of an omnipresent lack – lack of space, lack of the Other, lack of time, above all. “Time is luck”, says Isabella on several occasions to Sonny: a tragic refrain and curse of all of Mann’s heroes.

Surviving in the Flux

Miami Vice is above all a great film on the human condition in a time of flux. Everything progresses at top speed (the meetings, the love affairs, the reversals, the cars) but essentially nothing really moves forward. The general rumour of flux absorbs every modification of this flux, and dismisses events and characters with a noise from deep bottom. A trail of blood on the roadway (the suicide of the snitch, Alonzo (John Hawkes)), an echo on a radar or the noise of fingers snapping, are but nothing more than a short-lived imbalance of the global system. Whence the extraordinary and (paradoxical) inertia produced by a narrative so smitten with rapidity, as well as in the linking of sequences and shots, as in the execution of actions. The points of view become confused, the shots fall like unhooked links, but the general signal finishes by sweeping it along in the events that make it up. It traffics, it pulls, it circulates: Miami Vice is the point of flux against man’s point of view.

The use of HD allows Mann to forge a dense image, often opaque and viscous, which deepens the backgrounds and engulf the foregrounds. Thus, the characters gain in definition what they lose in contour, and thus in identity – visually, they free themselves with difficulty from the background and seem ceaselessly threatened with dissolution. This loss provokes an increased weight of the bodies (watch how they fall in the final shoot out), a constant swaying of space and, for the spectators, the feeling of a hypnotic pitching of shots. Deep water constitutes the primary substance of Miami Vice, a magmatic power that plays against the speed of the narrative and from which the individuals struggle and finally, failing that, they lose themselves. As a counterpoint to the chaos and confusion of human relations, Mann multiplies surface effects (bay windows, villas on the border of the sea) and sliding (off-shore, in the plane, in race cars). They are impeccable images from a world where survival depends on the capacity to remain on the surface (and superficial) and that allows consequently for only two positions: drowning (Sonny, the most infiltrated of the two) or weightlessness (Ricardo); either the temptation of the margin or the maintenance in the centre.

In the beginning of the film, Sonny and Ricardo pull-over Alonzo’s car, a snitch whose wife was just kidnapped. Sequence of panic on the edge of the highway: Alonzo wants to return home, see his wife and flee. “You don’t need to go home”, Ricardo says to him, since he knows it is already too late. Shot of Alonzo’s crushed face (“But they promised”), reverse shot on Ricardo’s (“They lied”). In the blurred passage from the cop’s face to the re-framing of the camera on the flow of the traffic, the man has thrown himself under a truck, leaving only a scarlet stain on the pavement. To become integrated in the flux is also to lose oneself therein.

The film closes as abruptly as it opened: Isabella escapes from the flux by the sea (the eternal utopia of Mann’s characters): “It’s magic”, says a fisherman about the sea near the beginning of Thief (1981), Sonny turns his back on the sea and returns to the flux. And loses himself therein. Life suspended on one side, perpetual flux on the other. No dead time or respite: the system runs at full speed but on empty, and possesses no other end than that of its own stability. To such an extent that one could, like Isabella, pass one’s entire life there: “It’s all that I know how to do; I’ve been doing that since I was 17”, she tells Sonny when the latter questions her on the possibility of an elsewhere, of an alternative life. The only thing that counts is the global balance of the system and its capacity to restore the unchanging order of things (disappearance of Jesus Montoya/death of Jose Yero, disappearance of Isabella/reappearance of Trudy, etc.). At bottom, between the beginning and the end of the film, nothing has changed. Like Frank (James Caan) at the end of Thief or Lowell Bergman (Al Pacino) in the last shot of The Insider, Sonny recedes in depth of the field, with his back to us, and disappears. In the world in flux that Miami Vice follows, the human is only an event, a lost atom in the multitude, similar to the one described by the hired killer in Collateral. It is either arrogance and/or naïveté of the couple, Sonny-Isabella, to have believed that the human could be stronger than the flux.

The men of Miami Dade only conform to the programs that pre-exist them, to respond to the electronic stimuli (a telephone call, a reaction). They turn out to be incapable of taking control of a disarticulated narrative that sometimes calls to mind, but in a less playful way, the game “Simon Says”, imagined by Jeremy Irons’ character in John McTiernan’s Die Hard: With a Vengeance (1995). Only Sonny manages it once with Isabella. You wouldn’t think it, and we’ll come back to it, but Miami Vice has also just laid the foundations for a new order of action films.

Identity of the World and of the Network

The post-urban (and post-human) world of Miami Vice is a confused, fragmented and controlled world that holds together only by the financial flux that crosses it and the electronic images (surveillance cameras, radars, computer screens, etc.) recreating the simulacrum. There is no other logic than that of offer and demand, of movement in all directions imposed by economic private interests. Little matter, then, whether the goods are legal or not, little matter, too, the nature of the market, since the film treats capitalism like a war (Jesus Montoya, the drug godfather, hooked on Bloomberg TV), with his exploitation of resources of the Third World (here, the Dominican Republic, Paraguay and Uruguay), the merciless elimination of rivals and its calculated violence. Impressive is the way in which Mann views the cartography of this world in flux, where one goes in the space of an edit from Brazil to Paraguay, from Miami to Geneva, but also from the Law to its underside, according to a logic of intensive and breathtaking permutation. The contemporary world such as the film describes is expressed in the sentiment of a generalized feeling, of an integral proximity of spaces and individuals, permitted by an ultra-sophisticated technological environment. It is a misleading proximity, since the solitude of beings (total in Miami Vice) gets worse as the virtual exchanges develop.

The idea of the network isn’t new in Mann’s cinema but it never reached this point of coincidence with the world. Already in Thief, Frank, independent burglar, knew how much his survival depended on his capacity to act outside of the Chicago mafia network. That is, until he swallows his motto (“My money goes in my pocket”) and accepts, for the sake of his family and his dreams, to make a deal with the Faust-like Leo (Robert Prosky). It is a fatal connection that ends in an immediate and devastating cataclysm of spaces (the jobs, his garage and his intimacy) that he had hitherto known how to partition. In Heat, no matter how much the frontiers between exterior and interior trembled, there still remains the possibility of taking shelter from the world. The friction between public and private spheres is frequent, the effects of one into another, but justly: the effects suppose an overstepping and consequently the existence of boundaries that are still active. It is moreover in organizing the alternation between one space and another, in exploiting this arrhythmia in the style of Jean-Pierre Melville, that Mann has forged his style, characterized by long contemplative stretches inserted in the heart of hyper-coded narratives (polar, adventure film, biopic, paranoid fiction, etc.).

In The Insider, the power of the network goes up a notch. Mann records the disappearance of the border separating the system (tobacco manufacturers) from the opposition (CBS, in fact, simple link in the great global economy), and confronted an old school journalist to a reticular cartography incipient in the heart of which this former student of Herbert Marcuse loses little by little his bearings. What is the secret at the hour of total transparence? Where does one place oneself when everyone is in the same boat? A first-rate response is issued by the CBS lawyer in the middle of the film, and which recalls that of Isabella in Miami Vice: “All that you see around you belongs to Jesus Montoya”, she says to Sonny who believes in the existence of an elsewhere. Does there exist a position exterior to the System? Otherwise, how to resist?

With Miami Vice, this tension between exterior and interior is completely reduced to the profit of a reticular world entirely subservient to the logic of the networks and the flux. Here, the spaces of resistance are disabled, almost nonexistent. Havana, haven of peace, is outside the flux and its exhausting topicality. In this sublime sequence, twelve minutes in weightlessness not a single one more, it is already time for Sonny to return (literally) to the dock. The counter space that Sonny and Isabella try to invent no longer holds together. Back in the flux, it explodes. The only possibility is to confuse the two, abolish the frontiers and submit to the rules of the network, like Ricardo and Trudy, lovers and co-workers. As Ricardo says to Alonzo: “You don’t need to go home” – and for a very good reason, because in Miami Vice home no longer exists. All that remains is an undifferentiated and homogenous zone, public and private, regulated and unstable.

The identity of the world and of the network explains why, according to a classical approach of the genre (undercover movie), what could have been one of the principal stakes of the film (How to preserve a cop’s false identity? How to make believe that one is another?) are settled very quickly. In Miami Vice, identity is no longer a question. “What difference is there between being infiltrated and being implicated up to your neck?”, as Ricardo more or less asks Sonny. The disconcerting facility with which the two cops shoulder the scheme of the complete Mafiosi expresses not only the indistinction of milieus but also the absolute reversibility of positions.

The fact that the priority is that of the network and not that of individuals implies the possibility of hiding oneself there, of disappearing in the intangible space of the Virtual and so to be nowhere located, which solves all problems of identity, not to mention the problems of alterity. (2)

An immense step is taken here from Heat, which, despite the impression of resemblance between the cop Hanna and the gangster McCauley, protects and maintains intact a principle of alterity, a difference of nature vis à vis the Law that prevents Mann from framing them together. (3) Heat was a film on reflection, the mirror effect, the temptation of the Other; Miami Vice is a film on confusion, indistinction and the equivalence of opposites. The cop is no longer the reversed double of the drug dealer, but his distant echo, his replica, even if on his last legs, Michael Mann once again half opens the door onto a world (Heat, the classic police story, the Law and its underside) in the process of becoming extinct. In Miami Vice, infiltration does not constitute an infringement of the general Law of a global system that has resolved contradictions and confused positions. In this obscure indecipherable without limits, what one really is (a cop, a crook) no longer matters. The only thing that counts is the trace that one leaves in the system, the stamp that one leaves there: back in Colombia where they have come to settle their first mission as carriers, Sonny and Ricardo fly a plane filled with drugs that is hidden in the wake of an official plane. Two distinct signals appear on the air control screen, two circles that overlap briefly before merging; two different engines for the radar, a single image. What difference is there between the Law and its underside? None, “Just a ghost”, says one of the radar controllers. No matter the differences as soon as one discharges the same image.

In Miami Vice, the image is not deduced from reality, but reality from the image. It is by it (parallel trajectories of two off-shore planes filmed at night) that Sonny and Ricardo identify the supplier who helps them to integrate into the Organization, it is by it again (two bodies intertwined on a dance floor) that Montoya understands the relation that unites Sonny and “his Isabella”, it is again it (the infra-red image of Jose Vero’s snipers that Lieutenant Castillo locates) that gives the send off for the final shoot-out.

The classical/modern conflict, essential in Mann, takes here an unexpected turn and puts Miami Vice undoubtedly at the origin of a new cycle in Mann’s work. The question is no longer, as in Manhunter (1986) or Heat, to evaluate what between two worlds is similar or different since, if disparity remains, it is in a negligible manner. From this point of view, classicism with its strong events (hold-ups, shoot-outs, marked positions, etc.), its simplification of the stakes and its resolution of an initial given situation is consumed: the leak in the heart of a governmental agency that launched the narrative will never be identified, the romance between Isabella and Sonny appears suddenly on the way and finally takes the upper hand, while, at the end, Montoya vanishes. From modernity and from American cinema of the 1970s, Miami Vice has kept a problematic rapport to action, between deflating (how many dismissed sequences and aborted conclusions) and overheating. But there is also the feeling of a complex and illegible world, in which it has become impossible to interact if not in a peripheral manner (the release of Trudy from the claws of the Aryen brothers, the elimination of Yero, etc.). The film progresses (too) quickly, but at a constant rhythm (which is to say the contrary of a classical temporality), as if nothing could carry it away or slow it down. The network demands it, the world of Miami Vice has lost its centre of gravity and seems devoted to a paradoxical movement: illusion of speed (or rather haste) but effect of being stuck. Heat and Collateral were centred around a dual relationship: two couples of characters – Hanna-McCauley and Vincent (Tom Cruise)-Max (Jamie Foxx) – whose intertwining constitutes the subject of the films, the point of equilibrium towards which they inexorably converge. Around what centre does Miami Vice turn? What finally is its point of anchoring?

Sonny and Isabella, The Axis of Desire